Physics: Einstein notation

At first glance, the Einstein notation may look intimidating, but this notation can be very powerful in vector calculus. This article is made for all the physics freshmen out there...

Today, I want to start talking about something very simple, yet very confusing for freshmen out there. The Einstein notations. I can assure you though, that you would not need to be an Einstein to understand this notation. Nevertheless, understanding the purpose of the notation is very much worth it, as such notation will be very powerful in electromagnetism, classical and continuum mechanics.

Explicit notation

To motivate this notation, I will start by demonstrating exactly why we need such notation. To do this, I would like to bring you back to my freshmen year.

Back during Theoretical Physics 1 of University Leipzig, I received a homework, which at first glance seems to be pretty innocent. The homework problem asks me to prove some vector identities, starting with the following:

$$a) \mathbf{A \cdot B} = \mathbf{B \cdot A}$$

$$b) \mathbf{A \times B}= - \mathbf{B \times A}$$

Fairly simple right? Riiiigghht...

Using my high school knowledge I tackle this problem as easy as lifting my hyperinflated ego.

$$\mathbf{A \cdot B} = A_x B_x+A_y B_y+A_z B_z$$

Using the commutativity of multiplication (i.e. for some number a,b ab=ba), then:

$$B_x A_x+B_y A_y+B_z A_z= \mathbf{B \cdot A} \blacksquare $$

Commutativity

For you who don't know, the properties above are called the commutativity of dot products and anti-commutativity of cross products respectively. Commutativity comes from the word commute or move around. Simply put, this tells you how freely some mathematical variables can move under some operation. So if some operation allows you to move around the order of variable you can say that the operation commutes. When you add "anti-", it generally means that the associated property on the operation will turn the result to negative.

Similarly, the anticommutativity of cross product can be proven the same way by expanding explicitly. What I used below is just the normal determinant.

$$\mathbf{A \times B} = \begin{vmatrix} \mathbf{e_x} & \mathbf{e_y} & \mathbf{e_z} \\ A_x & A_y & A_z\\ B_x & B_y & B_z \end{vmatrix}$$

$$=(A_yB_z-A_zB_y)\mathbf{e_x}+ (A_zB_x-A_xB_z)\mathbf{e_y} + (A_xB_y-A_yB_x)\mathbf{e_z} $$

Using the commutativity of multiplication again.

$$=-[ (B_yA_z-B_zA_y)\mathbf{e_x}+ (B_zA_x-B_xA_z)\mathbf{e_y} + (B_xA_y-B_yA_x)\mathbf{e_z}]$$

$$= -\begin{vmatrix} \mathbf{e_x} & \mathbf{e_y} & \mathbf{e_z} \\ B_x & B_y & B_z\\ A_x & A_y & A_z \end{vmatrix}=-\mathbf{B \times A} \blacksquare$$

Simple so far? I hope so. Now lets call the method we used, the "explicit notation". As one can see, it works, but now comes the rest of the problem.

$$c) \mathbf{A \cdot (B \times C)}= \mathbf{C \cdot (A \times B)}$$

$$d) \mathbf{(A\times B) \cdot (C \times D)}= \mathbf{(A \cdot C) (B \cdot D)-(B \cdot C)(A \cdot D)}$$

$$e) \mathbf{A \times (B \times C)}= \mathbf{B (A \cdot C)-C(A \cdot B)}$$

Now using the explicit notation, c) can still be solved and will be left as an exercise (You'll see a lot of this, especially in math books and lectures). However, to make my case and point, lets be naive and young, and work out d) with the explicit notation.

Let's seperate it into small pieces $$\mathbf{A \times B}\text{ and }\mathbf{C \times D}$$Then work out their dot products.

$$\mathbf{A \times B}= (A_yB_z-A_zB_y)\mathbf{e_x}+ (A_zB_x-A_xB_z)\mathbf{e_y} + (A_xB_y-A_yB_x)\mathbf{e_z}$$

$$\mathbf{C \times D}= (C_yD_z-C_zD_y)\mathbf{e_x}+ (C_zD_x-C_xD_z)\mathbf{e_y} + (C_xD_y-C_yD_x)\mathbf{e_z}$$

Hence the dot product between the two will be:

$$(A_yB_z-A_zB_y) (C_yD_z-C_zD_y) + (A_zB_x-A_xB_z) (C_zD_x-C_xD_z) + (A_xB_y-A_yB_x) (C_xD_y-C_yD_x)$$

Just looking at the first term.

$$(A_yB_z-A_zB_y) (C_yD_z-C_zD_y)$$ $$=A_yC_yB_zD_z+A_zC_zB_yD_y-A_yD_yB_zC_z-A_zD_zB_yC_y$$

In similar pattern, you can conclude that the entire product expanded is:

$$= A_yC_yB_zD_z+A_zC_zB_yD_y-A_yD_yB_zC_z-A_zD_zB_yC_y$$ $$+ A_zC_zB_xD_x+A_xC_xB_zD_z-A_zD_zB_xC_x$$ $$-A_xD_xB_zC_z+ A_xC_xB_yD_y+A_yC_yB_xD_x$$ $$-A_xD_xB_yC_y-A_yD_yB_xC_x $$

Factorizing some terms back in.

$$=A_yC_y(B_xD_x+B_zD_z)+A_xC_x(B_zD_z+B_yD_y)+A_zC_z(B_yD_y+B_xD_x)$$ $$-A_yD_y(B_zC_z+B_xC_x)-A_xD_x(B_zC_z+B_yC_y)-A_zD_z(B_xC_x+B_yC_y)$$

Now we would like to add some zeros , which the reason will be clear later.

$$=A_yC_y(B_xD_x+B_zD_z+B_yD_y)+A_xC_x(B_xD_x+B_zD_z+B_yD_y)+A_zC_z(B_zD_z+B_yD_y+B_xD_x)$$ $$-[A_yD_y(B_yC_y+B_zC_z+B_xC_x)+A_xD_x(B_xC_x+B_zC_z+B_yC_y)+A_zD_z(B_xC_x+B_yC_y+B_zC_z)]$$

Adding Zeros

Adding zeros mean in essence adding a term that cancels each other, for example: $$0=A_yC_y(B_yD_y)-A_yD_y(B_yC_y)$$

The above is nothing but:

$$=(A_xC_x+A_yC_y+A_zC_z)(B_xD_x+B_yD_y+B_zD_z)$$ $$-(A_xD_x+A_yD_y+A_zD_z)(B_xC_x+B_yC_y+B_zC_z)$$

$$=\mathbf{(A \cdot C) (B \cdot D)-(B \cdot C)(A \cdot D)} \blacksquare$$

Phew! We did it. However, one should notice by now how frustratingly long the proof is for d), let alone e). I remember back then, wasting my entire night stubbornly doing e) explicitly. Therefore, it would've been great if we find an alternative way to solve this more efficiently. Afterall, who'd want to remember all these vector identities!

Math Tips!

If you find yourself stuck with some abstract problem, using a naive method, by working things explicitly and to a specific case is not a bad idea! After figuring the underlying pattern, you can then generalize it to many cases.

Einstein Notation

Before introducing any symbols and complicated mathematical jargons, I would like to build this notation with you from the ground up. With this, I'd hope that we could dissect this so-called Einstein notation and understand it.

So first, let's go back to the very basic vector operations:

$$a) \mathbf{A \cdot B}=A_x B_x+A_y B_y+A_z B_z$$

$$b) \mathbf{A \times B}=(A_yB_z-A_zB_y)\mathbf{e_x}+ (A_zB_x-A_xB_z)\mathbf{e_y} + (A_xB_y-A_yB_x)\mathbf{e_z}$$

So now, how can we make it simpler? Let's start with the dot product. It should be pretty clear that there is a discernible pattern in a), so we can turn it into a summation. In here, I'd also like nummerize each component of the vector,i.e: $$\mathbf{(e_x,e_y,e_z)\rightarrow(e_1,e_2,e_3)}$$

$$\mathbf{A \cdot B}= \sum_{i=1}^{3} A_iB_i $$

Now let's say, ehhhmmm, not saying that I myself am this kind of person, just let's say, that I am...... cheap. Then I wanna save myself some money from buying pens. I ain't got time nor ink to waste it on some silly summation symbol. Fair point. Let's take it away.

$$\sum_{i=1}^{3} A_iB_i = A_iB_i$$

Looks neat. This is one of the conventions of the Einstein notation, and instead of using sum symbols, we use summation or dummy index, which indicates the summing of all indices.

Getting on to a more complicated case in the cross product. Now I hope you too, can still see a pattern in the explicit form. To make it even clearer, we'll dissect the components.

$$x:\mathbf{e_1}(A_2B_3-A_3B_2)$$

$$y:\mathbf{e_2}(A_3B_1-A_3B_1)$$

$$z:\mathbf{e_3}(A_1B_2-A_2B_1)$$

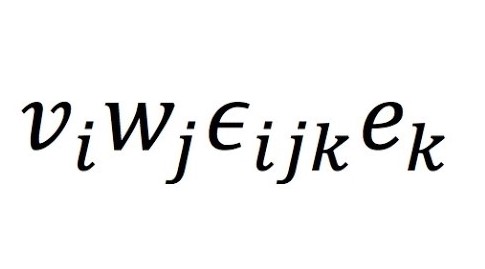

You could see that each term have the form: $$\mathbf{e_i} A_jB_k$$ The only difference is, for some sequence (i,j,k) associated to the term with sequences (1,2,3), (2,3,1), and (3,1,2) carry positive signs, while sequences (1,3,2), (2,1,3), and (3,2,1) carry negative signs, i.e.: $$\mathbf{e_1}A_2B_3\text{ and }-\mathbf{e_1}A_3B_2\text{ respectively.}$$

You could now see, that the sequences are just reorderings of the number 1, 2, and 3. These are called permutations of the collection of numbers {1,2,3}. If we consider an initial sequence of (1,2,3), the first three sequences are what we call even permutations because we only need to switch positions even numbers amount of time to get another sequence, while the latter is what we call odd permutations, for which the reason is already clear.

Example of permutations

$$(1,2,3) \rightarrow_1 (2,1,3) \rightarrow_2 (2,3,1)$$, since you need to switch the order twice, then it is an even permutation.

$$(1,2,3) \rightarrow_1 (1,3,2)$$, since you only need to do it once, then it is an odd permutation.

To continue with the spirit of Einstein notation, we're going to sum over all indices.

$$\sum_{i,j,k=1}^{3} \mathbf{e_i} A_jB_k$$

However, we already know from before, that for sequences of recurring numbers like (i,j,k)=(1,1,2) such terms do not exist. So we need some device that acts as an on-off button when such a sequence occurs. I'm going to start by introducing a symbol.

$$\epsilon_{ijk}= \begin{cases} 0, & \text{if i=j or j=k or i=k} \\ 1, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

Example: $$\epsilon_{112}=0\text{ and }\epsilon_{123}=1$$

Inserting this symbol to the previous sum means that every term that has a sequence of recurring number in the index will be multiplied by 0, or vanish, as we say it.

Of course, we're forgetting another thing. The term that has an odd permutation index carries a negative sign. We can fix that by adding another condition.

$$\epsilon_{ijk}= \begin{cases} 0, & \text{if i=j or j=k or i=k} \\ 1, & \text{if (i,j,k) is even permutation of (1,2,3)} \\ -1, & \text{if (i,j,k) is odd permutation of (1,2,3)} \end{cases}$$

In here, we've just formulated the Levi-Civita symbol/Epsilon tensor. You can see that we really condensed a whole lot of information in one beautiful symbol. Which is really why it's also called a tensor, which in layman terms is an object which stores information along different dimensions.

Levi-Civita symbol (part 1)

Definition

$$\epsilon_{ijk}= \begin{cases} 0, & \text{if i=j or j=k or i=k} \\ 1, & \text{if (i,j,k) is even permutation of (1,2,3)} \\ -1, & \text{if (i,j,k) is odd permutation of (1,2,3)} \end{cases}$$

Properties

$$\epsilon_{ijk}=\epsilon_{kij}=\epsilon_{jki}$$

$$\epsilon_{ijk}=-\epsilon_{ikj}=-\epsilon_{kji}=-\epsilon_{jik}$$

Everything is now taken into account. Using the convention of the summation index, we get:

$$\epsilon_{ijk} \mathbf{e_i} A_jB_k$$

To show that what we have so far is consistent, we'll try using our newfound notation to prove the two simple identities.

$$a) \mathbf{A \cdot B} = A_iB_i= B_iA_i= \mathbf{B \cdot A} \blacksquare$$

$$b) \mathbf{A \times B}= \epsilon_{ijk} \mathbf{e_i} A_jB_k = -\epsilon_{ikj} \mathbf{e_i} B_kA_j = - \mathbf{B \times A} \blacksquare$$

So our notation works! Beautiful. However, we are not done yet. Let's try working out the proof for d).

$$d) \mathbf{(A\times B) \cdot (C \times D)}= \epsilon_{ijk} A_jB_k \epsilon_{ilm}C_lD_m = \epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm} A_jB_k C_lD_m$$

A fair question to ask would be, $$\text{"How can I evaluate }\epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm}\text{?"}$$We can get the answer by thinking about the summing over the indices. You can see that the indices i is already used in the both of the epsilon tensor and since recurring number would lead to 0, we only have a choice of k not equal to j and i and m not equal to l and i (i.e. if i=1, then j=2 or 3 and k takes the rest). So we can seperate the sums for the case of :

$$\text{i) }j=l \implies k=m$$

$$\text{ii) }j=m \implies k=l$$

So what happens for case i)? If (i,j,k) is odd (or even) permutations of (1,2,3), (i,l,m) is then odd (or even) as well. Then the latter epsilon would always take the same value as the former, which means: $$\epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm} = 1\text{ (i.e. (-1)(-1)=1)}$$For the case ii), if (i,j,k) is an odd permutation of (1,2,3), then (i,l,m) is even (and vice versa). This would mean that the will two epsilons take opposite signs, which means: $$\epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm}=-1$$Then we can rewrite the d) in sum notation.

$$\sum\limits_{i,j,k,l,m=1}^3 \epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm} A_j B_k C_l D_m = \sum_{i=1 \text{, } j \neq k \neq i}^3 (A_jB_kC_jD_k-A_jB_kC_kD_j)$$

With this, you can see that the product of two epsilon tensors with 5 different indices, is in reality only dependent on 3 different summing indices, where both l and m is turned into either j or k (each indices takes on one value from set {1,2,3}). In the spirit of condensing information (and saving pen ink really..), we would like to find an on-off button again just like the epsilon tensor. With this I will introduce another symbol.

$$\delta_{ij}= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if i=j}\\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

What does the symbol mean in terms of indices? That means, if there is a summing of terms with index i and j, applying the tensor above means that all indices i not the same as j vanishes, or in other words, explicitly:

$$\sum_{i,j=1}^3\delta_{ij} A_iB_j= \sum_i^3A_iB_i$$

What we've just formulated is what we know as the Kronecker delta. So how is this symbol useful to evaluate the product of 2 epsilon tensor? Well, the vanishing indices do also in fact exist when applying the symbol. Hence the product is nothing but the following:

$$\sum\limits_{i,j,k,l,m=1}^3 \epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm} A_j B_k C_l D_m$$

$$=\sum\limits_{i=1, i \neq j \neq k, i \neq l \neq m}^3 (\delta_{jl}\delta_{km}-\delta_{jm}\delta_{kl}) A_j B_k C_l D_m$$

$$=\sum_{i=1 \text{, } j \neq k \neq i}^3 (A_jB_kC_jD_k-A_jB_kC_kD_j)$$

As you can see, we've evaluated the product of 2 epsilon tensors! In fact, you can get a more general case for 6 indices in the epsilon tensor product, however this will be left as an exercise.

Kronecker delta and Levi-Civita symbols (part 2)

Kronecker delta:

$$\delta_{ij}= \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if i=j}\\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

Levi-Civita symbols product:

$$\epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm} = \delta_{jl}\delta_{km}-\delta_{jm}\delta_{kl}$$

$$\epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{lmn} = \begin{vmatrix} \delta_{il} & \delta_{im} & \delta_{in} \\ \delta_{jl} & \delta_{jm} & \delta_{jn} \\ \delta_{kl} & \delta_{km} & \delta_{kn} \end{vmatrix} $$

Now with the formula of epsilon tensor products, we will prove our identity.

$$d) \mathbf{(A\times B) \cdot (C \times D)}= \epsilon_{ijk} A_jB_k \epsilon_{ilm}C_lD_m = \epsilon_{ijk} \epsilon_{ilm} A_jB_k C_lD_m$$

$$=(\delta_{jl}\delta_{km}-\delta_{jm}\delta_{kl})A_jB_kC_lD_m=A_jB_kC_jD_k-A_jB_kC_kD_j$$

$$=\mathbf{(A \cdot C) (B \cdot D)-(B \cdot C)(A \cdot D)} \blacksquare$$

Voila! An elegant and simple proof, something one should always strive for. With this proof, I would like to let you know in fact, that we're finished with building the basic blocks of Einstein notation. As for the identity in e), I would like you to do this as an exercise(It's trivial).

As a note to end, I'd like to let you know that there are many more conventions on the Einstein notation. What I have used here is the all-subscript convention, for simplicity. Another famous convention would be the superscript-subscript convention, which is definitely something to look into once you've studied differential geometry, as they use covariants and contravariants.

Hope you enjoyed my article, have fun with Einstein notation and good luck with your studies! :)

A.P.

P.S. For the sake of accessibility, I try to be as self-contained, as simple, and as explicit as possible, without it being too dumbed down. With this in mind, please do let me know if there is anything unclear, or just something outright wrong so that I could fix it,... and also improve the quality of my posts in the future. Thanks!